Thanks to @BronwynFryer for bringing this unforgettable weird song to our attention. Laurie Anderson grew up in Illinois but reached fame in the UK as a performing artist. In this, you’ll see why. She wrote O Superman! in the midst of the Iran hostage crisis; a rescue helicopter had just crashed and burned. Don’t settle for fake fixes, she’s saying; electronics and war machines won’t save us. It’s especially pertinent now as technology’s billionaires grow bigger and more numerous while the natural world around us, the real mother, is dying by inches. A PBS special on Extinction points out that at least ten percent of insects are gone. So what? you say—but insects are food for birds and fish, and birds and fish are dying too, and birds and fish are food for….uh-oh. It’s time to put our faith in our real Mother, the earth and her life cycle, or it' is us who will crash and burn. Her album, BIG SCIENCE, is just being re-released. Leave a message at the tone!

Greta Thunberg Doesn't Believe in a Climate Crisis; It's a FACT.

Sixteen-year-old Greta sailed to New York like a true Viking, because aviation is a major polluter, and we humans are just about out of time to save her generation’s future. We’re in the midst of a huge extinction, losing 600 species each day, she explains to Trevor Noah on The Today Show. Where she comes from, climate talk doesn’t focus on belief; .it’s a fact. Polar ice is melting, the ocean grows acidic. Tell your Congress member that our President and a Republican Senate may be a hoax, but the climate crisis is already underway. The future looks like California fires, Houston floods, Puerto Rico and Bermuda. Time to ACT. March with Students because our future is on the line September 20th!

Finding My True Wealth

Inside each of us is a story of money. It is about a lot more than numbers—it is about our sense of self-worth, power, influence, and security. I had an idyllic childhood in the forest of Vermont. I was nurtured by gentle and wise parents, and my sister and I would frolic through pastures punctuated by abundant wild strawberries. I was in fourth grade when I first felt poor.

It was picture day at school, exciting for me, dressed up in my fanciest clothes. Something wasn’t right at the breakfast table. My parents were arguing, because there wasn’t enough money in the bank to cover the $24 for the large individual portraits which we purchased each year. Mom wanted to borrow money from her best friend who was wealthy; Pa refused. He was too proud.

I went to school, my enthusiasm dampened. Our small class of only ten students had our group photo taken, and then everyone but me lined up to have their individual portraits taken. I slunk off to the corner, so embarrassed. I wished I was invisible. I was so ashamed that we couldn’t afford to have this photo taken like everyone else. I felt that pain of “not enough.”

Over the years, that feeling of “not enough” has haunted me. I have seen how money divides people in society, how wealthy people have privilege, and how few people talk about their poverty, as taboo as talking about sex or death.

When I was 22, I lived in Guatemala and shopped at beautiful markets from women wearing self-woven clothing, selling their handiwork and fresh produce. There wasn’t a price tag on anything! That made me very uncomfortable. They expected me to have a conversation about what the value was. For them, the relationship determined the value. The conversation was what gave meaning, it was back and forth. It was in the dynamic give-and-take that we settled on the price and made the exchange. I grew to love this way of being more intimate with people.

I returned from Central America and rented an apartment in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, statistically one of the very richest counties in the United States. Women in fur coats and diamonds came to apply for loans at the Bank of Jackson Hole, where I was executive assistant to the vice president. One month into the job, a stack of loan documents appeared on my desk. Suzy, the receptionist, told me that the previous CEO had just been accused of embezzling $1.5 million over the last decade. It was my job to copy the evidence against him. Looking through these forged documents, I imagined him on the final day of the annual federal audit of the bank when the lies were discovered. That night he tried to commit suicide. The anxiety and shame he must have felt! The fear of being discovered! What motivates someone to do this? Hunger for more. When is enough, enough? Greed compels us to seek more and more.

I returned to college to study money and graduated with my degree in international economics from Southern Oregon University. When my $30,000 in student loans came due six months later, I was shocked. While studying economics, I had neglected my own personal finance and money management. I took a course to learn these skills, and I began teaching workshops about creating a healthier relationship with money. Almost everyone I’ve taught is suffering in some way because of money, and there is extraordinary relief when we share our intimate stories and financial struggles.

In 2010, I said yes to the hardest job I’ve ever had. It’s physically and emotionally demanding, I’m on call around the clock, and there’s very little appreciation. I became a new mother. Motherhood is one of the least appreciated jobs, truly a labor of love. I’m supported by a loving husband and have healthy children and a helpful community. The first years of my two children were the hardest five years of my life. Much of the time I felt worthless. I was doing such valuable work, but I was receiving no money and very little acknowledgment from the outside world.

I remember nursing my infant in the wee hours of the morning. I heard a rumble in her diaper, and felt a familiar wetness on my hand. I took her to the changing table, and gently wiped that mustard colored poop from her back. There was no overtime pay for this work. It’s priceless. I’m grateful for the caretakers; the men and women who care for children and elderly parents are valuable beyond measure.

My children today are eight and five, and we cooperate to care for our land and each other. In my family we fluidly balance the offers and needs of everyone as we prioritize our resource use. This flow of sacred reciprocity is at the heart of family.

I now serve as the education director of the Post Growth Institute. We bring people together to barter, buy, and otherwise share and exchange their goods, knowledge, services, and skills. I am truly wealthy, as is my family, as is my community. Nature is generous, and so are my children. So are my neighbors. Each spring I transplant into my soil perennial flowers gleaned from the land of my neighbors. I will enjoy their beauty for years to come. As these flowers burst into bloom, they are valuable beyond measure because they were gifts.

The purple irises from Rachel’s garden, the dainty columbine from Deborah, the strawberries from Amy, raspberries and sunflowers from Carrie, the parsnips from Gideon, the echinacea from Ann; they are all stretching toward the light. The beauty of these plants unfurls in the warmth of the sun and our loving care. Much like our children. We moved onto our land nearly three years ago, and each spring is like welcoming familiar friends again as the plants emerge from their slumber.

Humans are made to tend to our gardens together. Each Sunday we have some neighbors over to work in the soil and feast together. We are so nourished by this time, brought back to the roots of belonging. We belong to this land, and she provides for us. The plants living on our acre by the creek swell and decay with the changing seasons.

There is something special about being in relationship that can’t be measured in money. This is what makes life worth living. Last Thanksgiving we hosted over 30 people, some family but mostly neighbors. I looked around at the people who had brought carefully prepared dishes with such love and generosity, at the kids running and laughing and playing games, at the people playing music and having intimate conversations. I smiled as I witnessed our spirit of generosity and love, and this to me is true wealth. Honestly, we are all wealthy beyond measure.

Think We're Past Sexism? Try Keeping a Diary

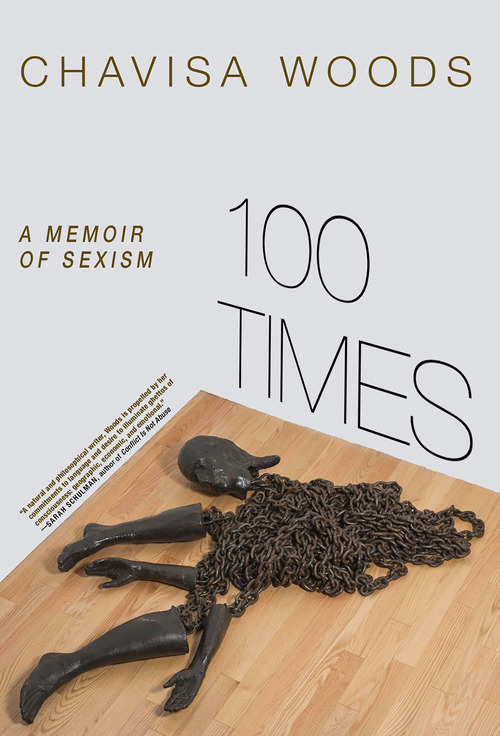

Chavisa Woods documents her personal experience with sexism in this new book from Seven Stories Press . This excerpt involves the police. But what if more os us kept track of small everyday ways of being discounted, harassed, or not counted?

This piece is from Women’s E-News today. Sign up to get their newsletter here.

When she was 5, the little boy Chavisa Woods was playing with pinched her butt. His mother, upon hearing the story, told her she probably liked it. When she was 36, a cab driver locked the doors and wouldn’t let her out until she gave him her phone number. In 100 TIMES: A MEMOIR OF SEXISM (Seven Stories Press; June 25, 2019), Woods lays out one hundred personal vignettes of the sexism, harassment, discrimination, and sexual assault she’s experienced in her life. The incidents, which range from lewd comments to attempted rape, take place when she was growing up in poor rural Southern Illinois, when she was working in St. Louis as a young adult, when she was living with her girlfriend in Brooklyn, and when she was a Shirley Jackson Award-winning author and three-time Lambda Finalist writing this book.

While Chavisa Woods chronicles these 100 stories to show how sexism and misogyny have impacted her life, something else happens simultaneously: she lays bare how these dynamics shape all women’s lives, and how relentlessly common they are. She underscores how thoroughly men feel entitled to women’s spaces and to their bodies, and how conditioned women are to endure it. It’s impossible to read 100 TIMES as a woman without cataloging one’s own “Number of Times.” As Woods writes in the book’s introduction, “It’s not that my life has been exceptionally plagued with sexism. It’s that it hasn’t.”

Excerpt:

#30

When I was twenty, still living in Saint Louis, two of my female lovers and one of my close gay male friends were all raped in the same year, two by strangers, and one by someone we knew. This didn’t happen to me, but going through this repeatedly with three unrelated people I was deeply intimate with in such a short time changed me forever.

One of my lovers was hospitalized and had to have stitches in the places where the man who assaulted her had bitten out chunks of her esh. She was a butch lesbian, and it was strange and painful seeing someone who seemed to be so strong and beautiful become so helpless. To me, she was the strongest, hottest, butchest girl in the Midwest. When she was around, I’d always felt safe. I’d never thought of her as someone who needed protecting. Every dyke wanted to be with her. She was a stud. e idea that a man could have rendered her powerless was surreal.

The man was a stranger who had pushed his way into her house as she was coming home from work. He told the police he was having an a air with her, and that her boyfriend had come home and caught them having sex, and chased him out, and that it must have been her boyfriend who beat her uncon- scious, and that she was claiming it was rape for her boyfriend’s bene t, so that he wouldn’t get mad at her.

She didn’t have a boyfriend. She’d never had a boyfriend. She was a gold-star butch. She was my lover, and probably had another girl on the side, too. But the police still believed him, somehow.

She was hospitalized for days, and the detectives on the case sympathized with her rapist. While she was in the hospital, one detective on the case even referred to him as “that poor man.” Because of this, and after several months of intense emotional discussions with a lawyer and arguments with the detectives, she decided not to go to court and press charges.

When she told me this, I thought, “we’re nothing to them.”

Queer women, that is. We don’t exist. They don’t see us.

They looked at this hot, fierce butch, and I wondered what they saw; a “larger,” plain woman with a short haircut who dressed unassumingly and for some reason needed to pathetically lie about being beaten and raped?

When she got out of the hospital she came and stayed with me, and we didn’t leave my bed for two days. It was a blue cocoon. I did my best to comfort her, but I was also young and emotional, and it was difficult in moments for me to give exactly what she needed. I was also hurting and not coping well. I did my best. I hope it is a good memory for her, because, for me, those days lying together and holding each other for hours on end are sacred.

I remember her bruises as blue, the room as blue, and the color of the air as blue. I realized, for the first time in our long relationship, that she must see me as powerful, too, if she came to me after that happened to her. I realized we were both powerful together, because we could actually see and value

each other. But that time left a blue mark on my heart also, as I realized, after everything that had happened that year, we were really nothing to the cops, nothing to so many straight men . . . nothing to the powers that order the world. Nothing.

Brooklyn-based writer Chavisa Woods is the author of the short story collection Things to Do When You’re Goth in the Country (Seven Stories Press, 2017), the novel The Albino Album (Seven Stories Press, 2013); and the story collection Love Does Not Make Me Gentle or Kind (Fly by Night Press, 2009). Woods was the recipient of the 2014 Cobalt Prize for fiction and was a finalist in 2009, 2014, and 2018 for the Lambda Literary Award for fiction. In 2018 Woods was the recipient of the Kathy Acker Award for Writing and the Shirley Jackson Award for Best Novelette.

Thanks for the flowers and brunch, but hey, listen....

"You Don't Know How Hard the World Can Be."

This 2018 film about young college women in pre-Roe v Wade Chicago makes clear what life was like when abortion was strictly a criminal operation, when everyone but the woman involved made decisions and had opinions about her womb and her sexuality. The Women’s Freedom Center in Brattleboro has an annual Women’s Film Festival each spring, and you can see Ask For Jane on March 30 at 6:00 pm at the New England Youth Theater. Gloria Steinem says every American should see this film—and we think our young people especially should see this.

One woman in the film speaks to her jailed companions about their naiveté, organizing an anonymous referral system for women “in trouble,” as it used to be called. “You don’t know how hard the world can be. But you’re about to find out.”

Jail was only part of it. Shaming continues to be a widespread weapon, but only for wombs, not for the penises involved. And beneath all that shame, violence still stalks us. The Women’s Freedom Center works with women who have been sexually assaulted or are in endangered by partner violence and abuse, which often includes financial abuse. The Women’s Film Festival is an educational fundraiser for the organization. Let’s keep on helping instead of judging. I think I remember hearing that it’s the Christian thing to do.