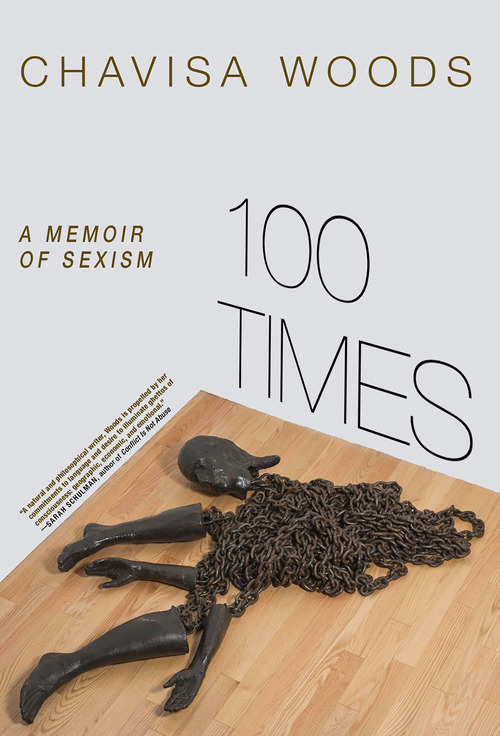

Chavisa Woods documents her personal experience with sexism in this new book from Seven Stories Press . This excerpt involves the police. But what if more os us kept track of small everyday ways of being discounted, harassed, or not counted?

This piece is from Women’s E-News today. Sign up to get their newsletter here.

When she was 5, the little boy Chavisa Woods was playing with pinched her butt. His mother, upon hearing the story, told her she probably liked it. When she was 36, a cab driver locked the doors and wouldn’t let her out until she gave him her phone number. In 100 TIMES: A MEMOIR OF SEXISM (Seven Stories Press; June 25, 2019), Woods lays out one hundred personal vignettes of the sexism, harassment, discrimination, and sexual assault she’s experienced in her life. The incidents, which range from lewd comments to attempted rape, take place when she was growing up in poor rural Southern Illinois, when she was working in St. Louis as a young adult, when she was living with her girlfriend in Brooklyn, and when she was a Shirley Jackson Award-winning author and three-time Lambda Finalist writing this book.

While Chavisa Woods chronicles these 100 stories to show how sexism and misogyny have impacted her life, something else happens simultaneously: she lays bare how these dynamics shape all women’s lives, and how relentlessly common they are. She underscores how thoroughly men feel entitled to women’s spaces and to their bodies, and how conditioned women are to endure it. It’s impossible to read 100 TIMES as a woman without cataloging one’s own “Number of Times.” As Woods writes in the book’s introduction, “It’s not that my life has been exceptionally plagued with sexism. It’s that it hasn’t.”

Excerpt:

#30

When I was twenty, still living in Saint Louis, two of my female lovers and one of my close gay male friends were all raped in the same year, two by strangers, and one by someone we knew. This didn’t happen to me, but going through this repeatedly with three unrelated people I was deeply intimate with in such a short time changed me forever.

One of my lovers was hospitalized and had to have stitches in the places where the man who assaulted her had bitten out chunks of her esh. She was a butch lesbian, and it was strange and painful seeing someone who seemed to be so strong and beautiful become so helpless. To me, she was the strongest, hottest, butchest girl in the Midwest. When she was around, I’d always felt safe. I’d never thought of her as someone who needed protecting. Every dyke wanted to be with her. She was a stud. e idea that a man could have rendered her powerless was surreal.

The man was a stranger who had pushed his way into her house as she was coming home from work. He told the police he was having an a air with her, and that her boyfriend had come home and caught them having sex, and chased him out, and that it must have been her boyfriend who beat her uncon- scious, and that she was claiming it was rape for her boyfriend’s bene t, so that he wouldn’t get mad at her.

She didn’t have a boyfriend. She’d never had a boyfriend. She was a gold-star butch. She was my lover, and probably had another girl on the side, too. But the police still believed him, somehow.

She was hospitalized for days, and the detectives on the case sympathized with her rapist. While she was in the hospital, one detective on the case even referred to him as “that poor man.” Because of this, and after several months of intense emotional discussions with a lawyer and arguments with the detectives, she decided not to go to court and press charges.

When she told me this, I thought, “we’re nothing to them.”

Queer women, that is. We don’t exist. They don’t see us.

They looked at this hot, fierce butch, and I wondered what they saw; a “larger,” plain woman with a short haircut who dressed unassumingly and for some reason needed to pathetically lie about being beaten and raped?

When she got out of the hospital she came and stayed with me, and we didn’t leave my bed for two days. It was a blue cocoon. I did my best to comfort her, but I was also young and emotional, and it was difficult in moments for me to give exactly what she needed. I was also hurting and not coping well. I did my best. I hope it is a good memory for her, because, for me, those days lying together and holding each other for hours on end are sacred.

I remember her bruises as blue, the room as blue, and the color of the air as blue. I realized, for the first time in our long relationship, that she must see me as powerful, too, if she came to me after that happened to her. I realized we were both powerful together, because we could actually see and value

each other. But that time left a blue mark on my heart also, as I realized, after everything that had happened that year, we were really nothing to the cops, nothing to so many straight men . . . nothing to the powers that order the world. Nothing.

Brooklyn-based writer Chavisa Woods is the author of the short story collection Things to Do When You’re Goth in the Country (Seven Stories Press, 2017), the novel The Albino Album (Seven Stories Press, 2013); and the story collection Love Does Not Make Me Gentle or Kind (Fly by Night Press, 2009). Woods was the recipient of the 2014 Cobalt Prize for fiction and was a finalist in 2009, 2014, and 2018 for the Lambda Literary Award for fiction. In 2018 Woods was the recipient of the Kathy Acker Award for Writing and the Shirley Jackson Award for Best Novelette.